Polish cinematographer Łukasz Żal is one of today’s most acclaimed visual artists in cinema, known for crafting images that resonate with emotional depth, historical texture, and poetic clarity. A graduate of the National Film School in Łódź, Żal first gained international recognition for his striking black and white work on Ida and Cold War, both of which earned him Academy Award nominations and cemented his reputation as a cinematographer of rare sensitivity and compositional rigor. He further solidified his reputation with The Zone of Interest, a visually daring and emotionally intense film that showcases his ability to blend meticulous composition with profound storytelling.

In Hamnet, directed by Chloé Zhao and adapted from Maggie O’Farrell’s beloved novel, Żal expands his visual language to meet the film’s unique demands, primarily using the ARRI Alexa 35, translating an interior, almost literary meditation on grief and love into a cinematic experience that feels both timeless and visceral. Rather than leaning on traditional period drama aesthetics, he uses observational framing, painterly compositions, and layered points of view to echo the novel’s shifting narrative voice, imbuing each image with a sense of presence and emotional truth.

His work on Hamnet is defined by thoughtful contrasts, from the intimate, nature‑drenched frames of Agnes in the forest to the structured, constricted compositions around Will in the classroom, and by a willingness to let the camera itself become a character in the story, at times detached and all‑seeing, at others deeply present in the emotional life of the family. Collaborating closely with Zhao, Żal explores light, movement, and space as tools to convey grief, love, and the fragile beauty of life, crafting a visual rhythm that lingers long after the credits roll.

With Hamnet sweeping TIFF’s People’s Choice Award and taking home the Golden Globe for Best Picture, One Lash Shot went behind the camera with cinematographer Łukasz Żal to explore the film’s breathtaking visual poetry.

Why did you want to become a cinematographer?

A good question. You know, when I was much, much younger—when I was, I think, 15 or 16—I had a really strong urge, you know, a real need to tell stories. I also loved telling stories to people.

I had some problems at school because my parents would get notes saying that Łukasz was just telling stories to other kids, and they weren’t listening to the teacher—they were listening to me. They said I was really ruining the lessons. And at a certain point, I really wanted to do something that would move people. I just wanted to create something that would move people, something I could show.

At that time, I didn’t know exactly what it would be, but I wanted to create something and tell stories that truly moved people. I tried many things. I tried theater, but they told me that my diction was terrible and that I should find something else. I tried drawing, but it didn’t work out—I was too impatient.

Then I found photography. I discovered my father’s camera and a little VHS camera, and I started filming and taking pictures.

When I became a kind of photographer and was finishing photography school, I started watching a lot of films and realized that I would not be able to move people with photography the way I could with film. I became jealous of filmmakers—photographers who could use sound and moving images as a much more powerful tool.

Then I started dreaming of becoming a cinematographer. It’s so interesting because now I realize—and not just now, but some time ago, with Hamnet and other films—how much I see people reacting. The audience, the people writing to me, the people crying… they really go through something. Hamnet is not a comfortable film. It sometimes puts viewers in a quiet discomfort zone.

But at the end, there is a kind of cathartic moment. That’s when I realized I had truly achieved my dream—the dream I had when I was a little kid, 15 or 16 years old.

I lived by the forest and would go there every afternoon. I loved being in the forest, and I dreamed—a lot. I dreamed deeply. And now, I realize I have made my dream come true with this film and others.

When I see how people react, it feels like my dream. That was my reason for becoming a cinematographer. And that’s also why my films, even when I was in school, were never very visual in the conventional sense.

Many of my friends made films that focused on cinematography—short films with striking visuals. But for me, film has always needed four legs: story, sound, music, and actors. Visuals were never the most important thing for me because they must always come from the story and the emotion.

My goal in making films—and what is most important to me—is capturing presence, those fleeting moments of magic, finding it even in something banal, absurd, weird, beautiful, or strange. I want to capture what is hard to express in words, the unspoken, the untold, something eternal. I always try, through my images, to create and transfer these feelings and emotions, which are difficult to articulate. That is the most important thing for me.

It’s not about beautiful light, picturesque images, or landscapes—it’s about transferring the feeling. What really puts a viewer there, helping them feel what the character feels. My goal is to help the director tell the story through images—not necessarily beautiful ones, because it doesn’t always have to be beautiful. Sometimes it can even be ugly. But if it serves the story and helps the viewer understand and feel, then that’s okay.

How did you and Chloé end up working together? And was there a single image, painting, photograph, or cinematic reference that became a visual “north star” for Hamnet? What did your mood board look like?

Yeah, you know, Chloé—when we first met, she invited me to dinner, and I didn’t know that she was going to propose this film to me. I just went there thinking we were going to have a general meeting.

Then she told me about the book, and I bought it immediately after our meeting and started working on it. I prepared a PDF, and the Production Designer, Fiona Crombie also prepared her PDF, as did Costume Designer, Małgosia Turzańska.

So, all of us were working independently, without Chloé, beforehand. Then we just sent our little books to Chloé, and she exchanged them so that everybody had each other’s work.

As for my book, I’m not sure how many pages it was, but it wasn’t very long. It wasn’t a big document; it contained references from films, some paintings, some photographs, and some ideas.

Basically, it was a small book with images, where every page had a bit of text. Some of my thoughts, for example, were in a chapter called Who is our camera? —discussing what kind of camera we were going to use and the types of cameras. There were also a few pages of images. Another chapter was a general one about how I would like to work on this film, where I explained my idea of having freedom in terms of camera movement.

So basically, there was a chapter where I explained how I would like to work—for example, that I would like to, you know, in every location and every place we were going to shoot, decide on the angle and what we see, whether in the forest or elsewhere. But I really wanted to move in a documentary manner, to be ready for everything. I wanted to use simple equipment—no steadicams or gimbals, no dollies or elaborate tableaus—but to have a handheld camera that was very mobile.

With a handheld camera, you can react and capture things as they happen. There was also a chapter about composition—how we were going to compose shots in a way that suggested what lies beyond the frame. We wanted to create open compositions and convey a sense of space to the audience. I wanted to show how Agnes experiences the world, how she sees things that are often unseen—how her vision is wider and more perceptive than most people’s. That’s why so much of our work focused on space, which was closely linked to sound.

In the book, there was also a chapter about the contrast between Agnes and Will, and how different their environments were—how she comes from the forest, and how we could treat the forest in our filming. We wanted to capture the forest as a living organism, to explore its structures, its life, and its texture.

I created this document based on the book, not a script, because there wasn’t a script yet. The book itself was written so beautifully—it wasn’t linear. There’s an omniscient narrator who knows everything, but then you suddenly jump into Agnes’ perspective or another character’s point of view, experiencing reality through their eyes. The descriptions of nature—the wind, the sun, the forest—were rich, sensual, and sometimes even sexual.

Reading the book and creating this document became a kind of navigation for the whole film. Filmmaking can feel like a small war: there’s so much technology, so many people, so much information to pass along, so many technical challenges, especially in difficult locations like forests. My document became like a little Bible, a set of personal rules—a “decalogue”—that I could return to, even though I sometimes broke them. It helped me stay focused and remember the original vision.

I think it’s amazing because those first ideas, when you read a book or script for the first time, are so important. Even if they seem simple, primitive, or silly, they capture your initial thoughts and feelings. Film involves so much logistics, planning, discussions, and meetings that it’s easy to forget your original ideas. That’s why writing them down and returning to them is so valuable.

Were there any scenes that were particularly difficult to shoot, emotionally or technically? And which was your favourite scene to shoot?

I think the most challenging part was the forest and the very first scene—the first shot where Jesse is by the tree and, you know, the hawk.

That was the most challenging because it was such a pivotal moment. For me, it’s always like that. Also, these are some of my favorite scenes.

Of course, I also love the ending, which really shows how we were working in a kind of documentary way. But let’s go back to the forest. I truly believe that the beginning of a film—the first seven to ten days—is the most important and crucial period, where the film starts to evolve and finds its shape. During this time, you always need to be very present, highly aware, and focused, observing everything that’s happening.

It’s often during this stage that you discover the form and language of the film, which makes everything easier later on. But the beginning, especially the forest scenes, was not easy. It was a real forest with lots of little holes in the ground, and it was also the most important moment where the characters fall in love.

First of all, we needed to capture this connection with them authentically. Paul and Jesse also asked for freedom—a freedom that meant we would not limit them with our cameras or equipment, but instead allow them to fully inhabit the moment. Capturing that, with all the equipment in the forest while creating a space that felt real and believable, was one of the most challenging aspects.

The first and foremost element was nature itself. For me, it was essential to portray nature not as beautiful, picturesque, or conventionally attractive, but as a living rhythm. I wanted to create the feeling that we are part of nature—that things are born, things die, and we are all part of this cycle.

The rhythm of nature became a kind of pulse within the film. Through it, the audience can feel that nothing lasts forever; everything that is born must eventually die. My goal was to present nature differently—as a structured, living organism—rather than just as scenery. That made the first period in the forest very challenging, but it’s also my favorite part of the film.

I also love the ending. It was amazing that Chloé discovered the ending just a few days before filming wrapped. Originally, it was supposed to be a bit different, but I love that she found it—and that our team was able to capture it.

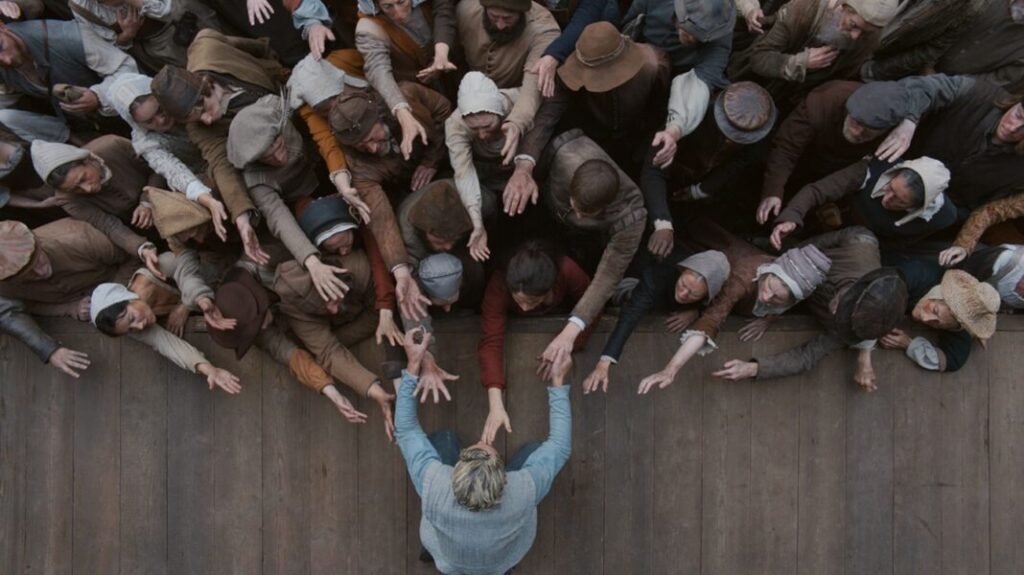

The beautiful moments were happening with the people, extras, and actors. I’m so happy that our team was able to work together and create an environment where we could shoot in a semi-documentary manner. Sometimes we would shoot “50/50,” which meant turning on the camera when people didn’t know, capturing life naturally.

I didn’t want it to feel like a traditional film with staged action. I worked hard to ensure it felt real. The ending, in particular, is a perfect example of this approach. It feels genuine and truthful—you can sense that what’s happening with the cast and extras is real.

I really love that we managed to work this way, and the ending is a great example of our approach to shooting the film.

[Author’s Note: Łukasz, I’ve admired your cinematography across so many films over the years, and this latest work feels refreshingly distinct from your previous projects. I’m excited to see what surprising visions you’ll bring to the screen next:)]