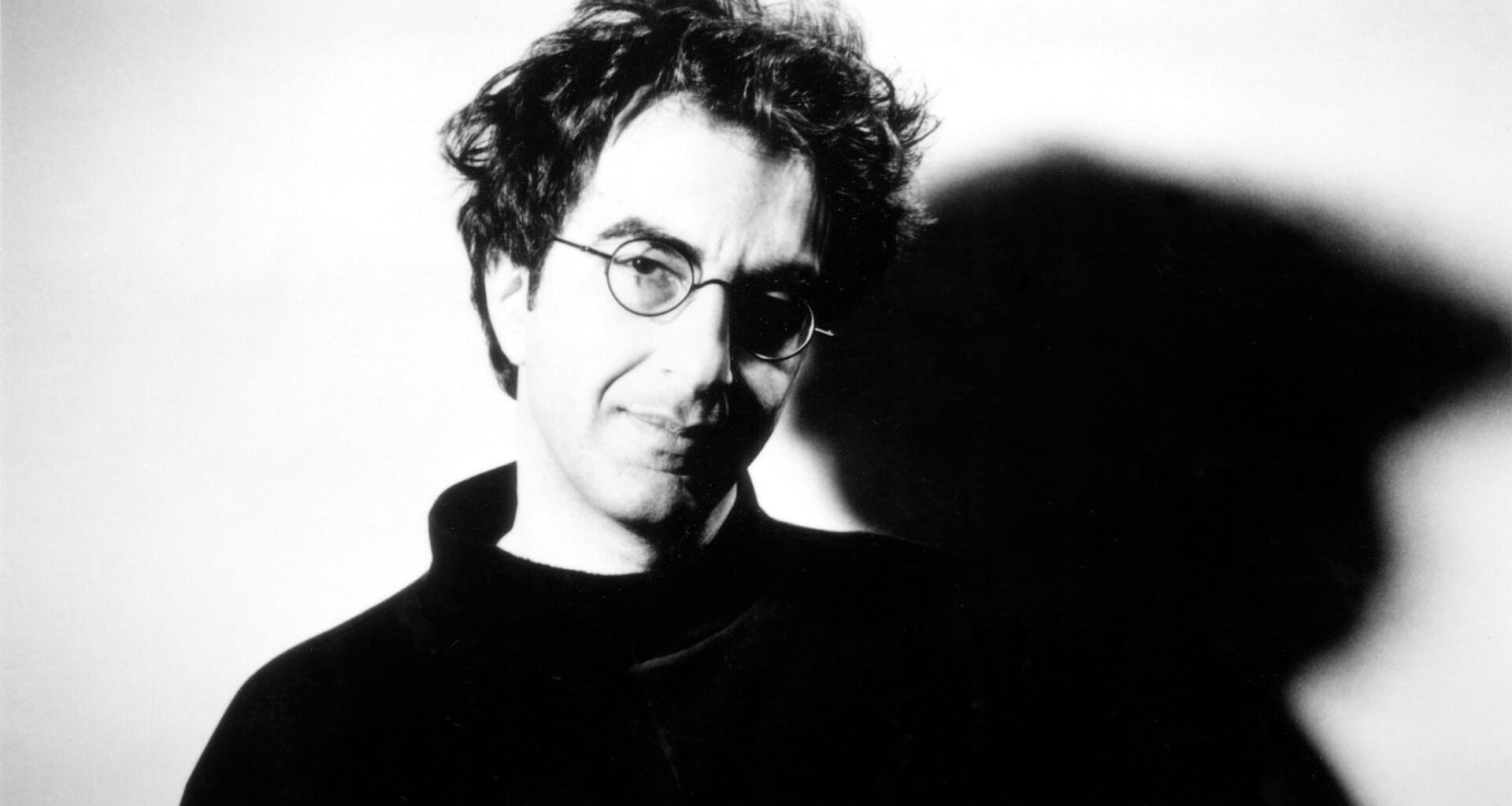

Back in 2009, I had watched Chloe— the film that marked the first collaboration between Atom Egoyan and actress Amanda Seyfried. Despite being directed by him, that story was not originally written by him. Fast-forward to 2024, Seven Veils marked their reunion, this time with Egoyan as the director and screenwriter.

With a chain of highly acclaimed films like Exotica and The Sweet Hereafter, Egoyan has been the recipient of several accolades over the years. But what makes Seven Veils stand out in his outstanding repertoire is that he combines his love for opera with filmmaking by writing a screenplay based on the age-old story of Salomé and basing a character whose history hauntingly resembles that of Salomé.

The story follows Jeanine, a young opera director who is unexpectedly tasked with remounting a Canadian Opera Company production of Salomé following the death of her mentor, resulting in moments of self-introspection during the directing process as she is forced to re-examine her convoluted personal connection with the project and thereby unwillingly encounter her darkest secrets.

The movie had its world premiere at the TIFF on September 10, 2023 and is set to release worldwide across theatres later this week.

One Lash Shot had the opportunity to speak with the legendary filmmaker Atom Egoyan about the behind-the-scenes of the opera-inspired Seven Veils.

How and when did you first discover Salomé? Was it through the one-act tragedy by Oscar Wilde, the one-act opera composed by Strauss that premiered at Dresden in 1905 or simply, the biblical references of John the Baptist?

It was through the play. I’d seen a production of Salomé in the late 80s in London that Steven Berkoff did, which was really stylized. It was a surprise because I thought I knew Oscar Wilde’s dramatic work. His other plays are very different. This is incredibly overwrought, the prose is very purple, and it sort of has a different tone.

Then, I encountered the opera because after Exotica, the then artistic director of the Canadian Opera Company, Richard Bradshaw, saw that film and thought the themes of the movie aligned with some of the themes that the opera presented. And, when I experienced the opera and I remembered seeing the play in London, it all came together. I thought that this was so close to me in terms of what happens when I am frustrated, surveillance issues and all the stuff that was very much part of my films at that time.

So, it was a really great experience as someone who started in theatre and really was writing plays, and then, started making films— it was a great way to go back to theatre.

This production was first mounted in 1996 in Toronto and then it sort of took off. It was very successful and it went to a number of different places.

Then the Canadian Opera Company decided that they were going to remount it two years ago. Yes! Exactly two years ago, in February 2023!

Once I understood that they were going to remount it, I began to think that it feels old now— that was 1996, now the times have changed. There are so many things that I felt the production was addressing at that time, but I wanted to refresh it. I couldn’t do that because you don’t have the time while remounting to change things that much. But then I began to think of this story and these characters and how I could remount it through a film that used that production. That’s where it began.

Then the character of Jeanine emerged. She became very powerful to me. Especially, when I thought of Amanda— we said we would work together again after Chloe and this seemed to be the perfect role.

Chloe was some time ago and the opera was some time ago. And, there was this idea of going back to a creative relationship.

All these things began to merge into the screenplay. It was a very, very layered, rich experience, unlike anything I’d ever had before. It was crazy— it was really difficult to balance the two schedules of having the opera at the same time as we were filming. But it felt it was worth it, right? It was worth the risk and I am really proud of it. Super proud of it.

You directed Seven Veils while also directing the opera within the movie for a live audience. How did you manage shooting most of the footage in a two-week period?

Yeah! It was an intense shooting experience I had for a number of reasons. There was a lot of stuff happening. And, it was improbable that the schedule would work out; that we’d have the financing in place just in time to make this happen. It fell apart at one point.

Then, having a major star who is very busy. Saying that she needed to do it on these particular days— we had no flexibility. I remember she was presenting at the Golden Globes at one point, she had to get back on the plane and come back on an overnight flight to be on set the next day.

And then there was like Covid. It just felt like there were a lot of factors kind of working against it, but if they could all come together, we would create this crucible that we’d be able to explore this material in a way that was very vital and urgent.

That’s what we needed. It felt like this production was dealing with so many issues and bad behaviour. If I could construct a story where I was able to work with the imaginations of an opera company— a world I know very well— and create this character who is unusual, I would choose to do so. Because, most of the time when people deal with trauma, it bubbles up out of nowhere.

In this case, it is clear from the beginning that everyone knows her history with the story, her history with the original director of the story. But what she can’t anticipate is how the actual creative process is going to create this re-traumatization and a very different sort of setup and circumstances.

I think what drives it is just one’s excitement— this need to make the film. This is an opportunity that cannot be passed up— you have to explore it. And, you have to push and make sure that everything works. It’s delusional. Like most of the creative process is. If you look at it, you’ll say, “It’s not realistic to think these things are all going to fit.” But when they do, it’s a miracle and you are just thankful.

As you mentioned, your first mounting of Salome was in 1996. Fast forward to the time you were shooting Seven Veils; wasn’t that the seventh time you remounted it? How were you able to navigate the lead character alongside Amanda, especially considering the self-introspection and sensitivity issues that Jeanine was forced to encounter while striving to follow her mentor Charles in Seven Veils?

Yes, that’s correct!

A lot of it is about trusting the intuition of the actor. If you are able to contextualize what the context is that they are in, you have to trust that they will intuitively rise to that.

You can direct it to a point, but there are the small details.

So, there are things that she is doing, which I can look at now from some distance, and I go like, “That’s miraculous that she was able to discover it and create a detail emotionally.” And that’s just her instrument. She’s able to do that because she is such a good actress. She’s able to do that because she is such a good actress. She’s able to be in a moment in a way that I can’t because I am not a performer.

My skill is being able to organize these things, put them together and cast it in the right way.

But then you are hoping that these amazing humans are able to feel things in this kind of presence and so clearly just transmit that. I need to trust their ability to do that.

Just like the singers in the movie— I can direct them to an extent, but what they are doing with their voices in that moment is so precious and unworldly and unlikely. When it occurs, you are just in awe. Like anyone else.

In a dialogue, Jeanine mentions that Charles’ favourite spot was the rehearsal bridge that connects the stage to the audience- the heart of the action. Is that your favourite spot in the Four Seasons too?

I must admit, we don’t see it when the orchestra is playing. But to be on that bridge, right over the orchestra and to see that music being generated, and then turn your head to see the stage, and then to turn your head and see the audience— it is a very powerful place.

I am glad that people actually picked up on it because it is an unusual space. It disappears once the show opens. It’s not there when you are actually performing.

It is just there during rehearsals so that you have a conduit between the director’s desk and the stage. You can get back and forth quite close. But it’s really an ephemeral space. It exists now in our imagination as we describe it, but it’s given a visual representation.

I am so happy that that stuck with you. It’s good!